Mulk Raj Anand

Table of Contents

-

- Life Introduction of Mulk Raj Anand

-

- Early Life Education

-

- Career

-

- Biography of Mulk Raj Anand

-

- Political Orientatation

-

- Later Life

-

- Works of Mulk Raj Anand

-

- Notable Awards

Life Introduction

Life Inroduction

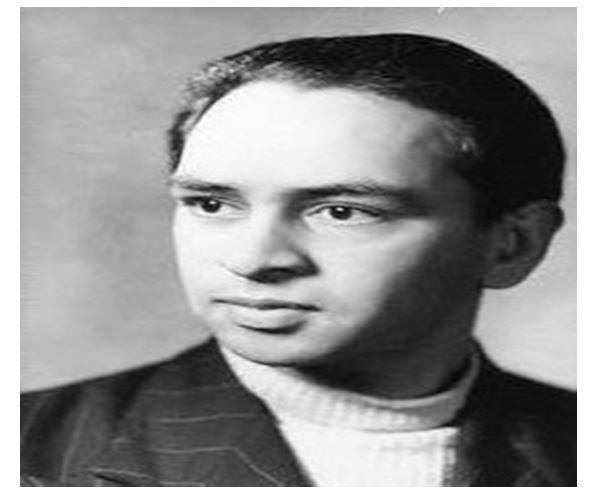

Mulk Raj Anand (born December 12, 1905, Peshawar, India [now in Pakistan]—died September 28, 2004, Pune) was a prominent Indian author of novels, short stories, and critical essays in English who is known for his realistic and sympathetic portrayal of the poor in India. He is considered a founder of the English-language Indian novel.

The son of a coppersmith, Mulk Raj Anand graduated with honours in 1924 from Punjab University in Lahore and pursued additional studies at the University of Cambridge and at University College London. While in Europe, he became politically active in India’s struggle for independence and shortly thereafter wrote a series of diverse books on aspects of South Asian culture, including Persian Painting (1930), Curries and Other Indian Dishes (1932), The Hindu View of Art (1933), The Indian Theatre (1950), and Seven Little-Known Birds of the Inner Eye (1978).

A prolific writer, Mulk Raj Anand first gained wide recognition for his novels Untouchable (1935) and Coolie (1936), both of which examined the problems of poverty in Indian society. In 1945 he returned to Bombay (now Mumbai) to campaign for national reforms. Among his other major works are The Village (1939), The Sword and the Sickle (1942), and The Big Heart (1945; rev. ed. 1980). Mulk Raj Anand wrote other novels and short-story collections and also edited numerous magazines and journals, including MARG, an art quarterly that he had founded in 1946.

He intermittently worked on a projected seven-volume autobiographical novel entitled Seven Ages of Man, completing four volumes: Seven Summers (1951), Morning Face (1968), Confession of a Lover (1976), and The Bubble (1984).

Early life and education

Mulk Raj Anand was born in a Hindu family of Kshatriyas on 12 December 1905 in Peshawar, the central city of Northwest Frontier Province, now in Pakistan. He was the third of five sons of La1 Chand, a silversmith turned sepoy. Anand’s father belonged to the Thathiar caste. People of Thathiar caste were workers of copper and silver. Lal Chand left his hereditary occupation to attend school.

He learnt English, took a British military examination and served in cantonments including Sialkot. Ferozepur, Peshawar, Mian Mir, Nowshera and Malakhand. He was appointed a head clerk, attached to the Thirty-eighth Dogra Regiment. He was said to be the only literate man in the whole regiment. He was a worldly man, highly ambitious for his sons’ education and economic status.

As an Arya Samaji, Anand’s father also served as president of the Nowshera Samaj from 19 10 to 19 13. ~s’the society incurred the hostility of the British Officials for its rebellious activities, Lal, fearing the displeasure of his superiors and the British rulers in India, withdrew from the group Mulk Raj Anand inherited from his father a professional artisan’s industry and minute attention to detail as also the revolutionary temperament.

Mulk Raj Anand (1905-) Anand’s mother came from a devout Sikh peasant family of Sialkot. a part of Central Punjab. She was a religious woman who had a great faith in orthodox beliefs. She had a vast knowledge of folk tales, having heard them in her childhood from her own mother, as also legends, fables, myths and other narratives of gods, men, birds and beasts. “So sure was my mother’s gift for storytelling,” says Anand, “that sometimes I found myself rapt in her tales with an intensity of wonder.” .

The first twenty years of Mulk Raj Anand’s life seem to have been spent in the Punjab area After passing his matriculation in 1920, Mulk Raj Anand entered Khalsa College, Amritsar. He joined non-violent struggle against the British government and courted arrest. His early recollections focus on two cantonments, Mian Mir and Nowshera In 1925. he graduated from Punjab University with Honours in English.

The first break in Anand’s life came when he received a scholarship for research in philosophy under Professor Dawes Hicks in London. It is here that he started creative writing. In 1926, he completed dissertation on the thought of great philosophers: John Locke. George Berkeley, David Hume and Bertrand Russell. In- 1928, he was awarded Ph D degree by London University. He then associated with T.S. Eliot’s literary periodical The Criterion.

Mulk Raj Anand’s literary career was launched by a family tragedy arising from the rigidity of India’s caste system. His first prose essay was a response to the suicide of an aunt excommunicated by her family for sharing a meal with a Muslim woman. His first novel, Untouchable, published in 1935, is a chilling exposé of the lives of India’s untouchable caste which were neglected at that time.

The novel follows a single day in the life of Bakha, a toilet-cleaner, who accidentally bumps into a member of a higher caste, triggering a series of humiliations.

Bakha searches for salve to the tragedy of the destiny into which he was born, talking with a Christian missionary, listening to a speech about untouchability by Mahatma Gandhi and a subsequent conversation between two educated Indians, but by the end of the book Anand suggests that it is technology, in the form of the newly introduced flush toilet, that may be his savior by eliminating the need for a caste of toilet cleaners.

Untouchable, which captures the vernacular inventiveness of the Punjabi and Hindi idiom in English, was widely acclaimed, and won Anand his reputation as India’s Charles Dickens. The novel’s introduction was written by his friend E. M. Forster, whom he met while working on T. S. Eliot‘s magazine Criterion. Forster writes: “Avoiding rhetoric and circumlocution, it has gone straight to the heart of its subject and purified it.”

Dividing his time between London and India during the 1930s and 40s, Anand was active in the Indian independence movement. While in London, he wrote propaganda on behalf of the Indian cause alongside India’s future Defence Minister V. K. Krishna Menon, while trying to make a living as a novelist and journalist.

At the same time, he supported Left causes elsewhere around the globe, traveling to Spain to volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, although his role in the conflict was more journalistic than military. He spent World War II working as a scriptwriter for the BBC in London, where he became a friend of George Orwell.

Orwell’s review of Mulk Raj Anand’s 1942 novel The Sword and the Sickle hints at the significance of its publication: “Although Mr. Mulk Raj Anand’s novel would still be interesting on its own merits if it had been written by an Englishman, it is impossible to read it without remembering every few pages that it is also a cultural curiosity.

The growth of an English-language Indian literature is a strange phenomenon, and it will have its effect on the post-war world”.] He was also a friend of Picasso and had paintings by Picasso in his personal art collection.

Anand returned to India in 1947 and continued his prodigious literary output here. His work includes poetry and essays on a wide range of subjects, as well as autobiographies, novels and short stories. Prominent among his novels are The Village (1939), Across the Black Waters (1939), The Sword and the Sickle (1942), all written in England; Coolie (1936) and The Private Life of an Indian Prince (1953) are perhaps the most important of his works written in India.

He also founded a literary magazine, Marg, and taught in various universities. During the 1970s, he worked with the International Progress Organization (IPO) on the issue of cultural self-awareness among nations.

His contribution to the conference of the IPO in Innsbruck (Austria) in 1974 had a special influence on debates that later became known under the heading of the “Dialogue among Civilisations”. Anand also delivered a series of lectures on eminent Indians, including Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore, commemorating their achievements and significance and paying special attention to their distinct brands of humanism.

His 1953 novel The Private Life of an Indian Prince is autobiographical in the manner of the rest of his subsequent oeuvre. In 1950 Anand embarked on a project to write a seven-part autobiographical novel titled Seven Ages of Man, of which he was only able to complete four parts beginning in 1951 with Seven Summers, followed by Morning

Face (1968), Confession of a Lover (1976) and The Bubble (1984). Like much of his later work, it contains elements of his spiritual journey as he struggles to attain a higher degree of self-awareness. His 1964 novel Death of a Hero was based on the life of Maqbool Sherwani. It was adapted as Maqbool Ki Vaapsi on DD Kashir.

Anand was associated with the BBC‘s Eastern Service radio station in the 1940s where he broadcast literary programs including book reviews, author biographies, and interviews with authors like Inez Holden. In a multi-part broadcast program that he hosted, he discussed poetry and literary criticism, often calling for working class narratives in fiction.

Biography of Mulk Raj Anand

Mulk Raj Anand, a renaissance man, was a novelist, essayist, critic, and thinker. M. K. Naik compares him to an “august and many-branched” banyan tree. The most dramatic moment in the early and sudden recognition of Anand as a novelist came with the publication of two novels, Untouchable (1933) and The Coolie (1936).

Untouchable deals with the ignominious problem of caste and untouchability in Indian society and includes a preface by E. M. Forster. Noting Anand’s power of sharp observation, objectivity, and directness, Forster remarks, “Untouchable could only have been written by an Indian, and by an Indian who observed from the outside.” Forster goes on to observe: “No European, however sympathetic, could have created the character of Bakha, because he would not have known about his troubles.

And no Untouchable could have written the book, because he would have been involved in indignation and self-pity.” Anand carries over this idea of human exploitation and social injustice in the characterization of Munoo in The Coolie.

In a larger sense, untouchable and coolie are interrelated metaphors of universal human degradation, cruelty, and suffering. Anand further developed the metaphor of coolie and the sociopolitical issue of class structure in Two Leaves and a Bud (1937).

Anand’s first three novels, which appeared successively within a short period of three years, claimed for him the position of a progressive and unswerving advocate of the lower echelon of society–the oppressed, the victimized, and the dispossessed. In the four novels that followed, Anand persistently showed his preoccupation with man’s inhumanity to man.

Anand’s career can be divided into two stages: the Anand of the colonial period, who steadfastly critiqued class exploitation, the caste system, colonialism, imperialism, fascism, and racism; and the Anand of the postindependence era, who spread his energies and interests into several directions that became open with the new aspirations of India as a sovereign state.

The Village trilogy–The Village (1939), Across the Black Waters (1940), and The Sword and the Sickle (1942)–deals with the three stages of growth of Lal Singh, a peasant’s son, in the midst of the stormy struggle for India’s independence and the various sociopolitical events that faced Europe in the 1930s and 1940s.

Whereas The Village gives the reader the true picture of Indian village life, Across the Black Waters is a representation of Lal Singh’s and his friends’ experiences of fighting against the Germans in France during World War I. “Anand’s achievement in the first two novels of the Trilogy,” remarks Meenakshi Mukherjee, “has not been surpassed by an Indo-Anglian novelist.” The first and only fictional account of the use of Indian troops in World War I, it raises the moral issue of the deployment of Indian troops in a British war.

But The Sword and the Sickle (the title suggested by George Orwell from one of William Blake’s poems) is literally and metaphorically a dramatization between the “sword” (the landlords) and the “sickle” (the peasants). Widely acclaimed as a successful novel, The Big Heart (1944) is a dramatic enactment of the conflict between the machine and laborers, the laborers in this case from the community of thathiars (coppersmiths), who are threatened with displacement from their hereditary profession.

The Big Heart also replicates the fierce conflict that took place in Europe between modernity and tradition.

These seven novels of the pre-Independence era–all published in England–have given Anand a well-merited position as a successful and radical novelist. They provide a mirror image of Anand’s active interest in the nationalist movement; his understanding of India’s social and political problems; his opposition to colonialism, imperialism, and fascism; his uncompromising sympathies with the lowest part of humanity; and his analysis of all forms of social injustice and dehumanization.

They also reflect the formation of the early Anand and the evolution of his personality during the pre-Independence era.

Born 12 December 1905 in Peshawar to a Kshatriya family–the second highest caste in the Hindu caste system–Anand was educated mostly in cantonment schools and later at Khalsa College, Amritsar (Punjab University). Anand’s father, Lal Chand, began life as a coppersmith but became a military clerk in the British Indian army. His mother, Ishvar Kaur, a peasant girl from a Sikh family, had a religious bent. Mulk Raj was the third of the five children born to the Anands.

Anand graduated in 1924 from Punjab University with an honors degree in English and became deeply involved in the nationalist movement. A few important events of the Amritsar period (1921-1924) that left a permanent mark on Anand were his active participation in the Civil Disobedience movement, the death of his nine-year-old cousin Kaushalya, and his love for Yasmin, a married Muslim woman who ultimately committed suicide. Anand enrolled at the University of London in 1925 for a Ph.D. in philosophy under the supervision of G. Dawes Hicks, a famous Kantian.

The twenty years Anand spent in England were ones of an impressive intellectual and professional blossoming. By the time he had completed his Ph.D. in 1935, he had developed intimate relationships with prominent English writers and critics. Anand’s deep immersion in European intellectual thought and his direct involvement in English politics helped him to understand the British mind, especially in relation to its response to India’s nationalistic aspirations.

In Conversations in Bloomsbury (1981), Anand reproduced from his memory his conversations with writers such as T. S. Eliot, Forster, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, and Aldous Huxley regarding the fundamental issues of freedom and equality for the Calibans of the Empire. During his stay in England, Anand met the English intelligentsia of the Right and the Left. For example, critic Bonamy Dobree, who took great interest in Anand and helped him ungrudgingly, was a professed Tory.

Herbert Read, who liked Anand’s first important work, Persian Paintings (1930), and to whom the work was dedicated, was an anarchist. Dobree greatly admired Anand’s essay on Sarojini Naidu included in The Golden Breath: Studies in Five Poets of the New India (1933). Read also admired The Hindu View of Art (1933), Anand’s work that was written under the early influence of Ananda Coomaraswamy and Sarvepalli Radhakrishanan and carries an introductory essay by artist Eric Gill.

The two essays “The Religio-Philosophical Hypothesis” and “The Aesthetic Hypothesis” clearly show young Anand’s aesthetic sensibility and his early search for philosophical and aesthetic formulation of art based on the religio-philosophical view of the Indian aesthetic of rasa, bhava, and ananda. Some of Anand’s expositions come fairly close to Coomaraswamy’s argument, and Anand’s philosophical training enabled him to look at history as philosophy of history and at art as philosophy of art.

The publication of The Lost Child and Other Stories (1934), Anand’s first published work of fiction, was facilitated by Gill’s generous efforts. The story “The Lost Child” focuses on the desires of a young boy who gets lost at a festival. (Anand eventually transformed the story into a successful movie, which he himself directed and which was produced by the government of India.) In his autobiographical essay Apology for Heroism: An Essay in Search of Faith (1946), Anand revealed that he had undergone a dramatic change between 1934 and 1946.

He became greatly involved with the problems of the oppressed people of the world, especially the British working class, but closer to his heart were the poverty of the Indian masses and tyranny of the British in India. Two works that ensued from Anand’s encounter with Marxism are Marx and Engels on India (1933) and Letters on India (1942). The latter was also based on Anand’s own experience with the British colonial governance of India and reflects his strong commitment to India’s freedom.

In his review of Letters on India, Orwell defended Anand for his anti-British position, and Read also praised the book, but a few of Anand’s English friends were not happy with the radical positions he took in it.

The Apology for Heroism is a lucid statement of Anand’s social, political, and philosophical thought. His Marxism enabled him to see “not only the history of India but the whole history of human society in some sort of inter-connection.” The work is also part of the history of ideas, European and Eastern, that had preoccupied Anand’s mind and that enabled him to survive the troublesome and despairing 1930s, the “pink decade.

” Rejecting the ideas of disinterestedness and escapism in art and aloofness and alienation of the artist in society, Anand boldly embraced Percy Bysshe Shelley ‘s idea of the poet as the “unacknowledged legislator of mankind.

” The function of art, according to Anand in Apology for Heroism, is not to escape from life and society but to communicate “the most intense vision of life.” In the postscript to the work Anand clearly and forcefully defines his commitment to humanism based on the “world of values,” but not divorced from the world of facts.

Believing in the whole man and in his ability to reconstruct a new progressive social order, and admiring the humanity of Rabindranath Tagore, Mohandas Gandhi, and Radhakrishanan, Anand stresses the recognition of human dignity as a directional force in human relationships.

He also stresses love, karuna (compassion), and bhakti (devotion) as central values in the transformation of human conduct and the development of higher consciousness as a basis for the search for the truth of human life.

In attempting to strike a synthesis between the world of appearance, illusion, or maya and the world of reality, truth, beauty, and good, Anand concludes the postscript with words from the Mahabharata (A.D. 400): “Truth is always natural with the good–Truth is duty. Truth is penance–Everything rests on TRUTH.”

Anand’s humanism, especially with its central values of love, karuna, bhakti, and tenderness, has a spiritual dimension, for it exceeds the structural limits of scientific humanism and combines the developments of head and heart.

Anand’s socialism, despite its roots in British liberalism and socialism, has a spiritual dimension: “socialism,” Anand explains in Apology for Heroism, “implies a spiritual change which will evolve its own internal checks, its own standard of values and its own ideals.” Significantly, Anand’s humanism has tilted toward the depressed, the dispossessed, and the exploited.

One might see in it his effort to achieve an eclectic synthesis of various ideologies of social reconstruction, including Marxism, socialism, and humanism. The impact of the Gandhian ideas of moral and social reconstruction can also be seen.

Anand’s realism derives its basis from his humanism. His attempt to transfuse history, ideology, and value in his fiction does not in any sense mean a compromise with tradition, nor does it show any slippage in his commitment to revealing human ugliness and depravity.

He has stated candidly that the rediscovery of Indian ideals is as meaningful as is the rediscovery of European traditions. In Apology for Heroism, Anand undertakes an intellectual analysis of the significant ideas in the two cultural traditions in an attempt to seek a broader basis for his conception of humanism.

He rejects fascism, colonialism, imperialism, racism, war, and oppression and prefaces his own concept of humanism with universalism and Indian religious-metaphysical values. Anand’s exposure to Western intellectual thought helped him also to see his own heritage somewhat critically and objectively.

Untouchable and The Coolie are novels in which the central characters typify suffering humanity. Whereas Bakha is an untouchable, an outcaste in the Hindu caste structure, Munoo, the coolie, and Gangu are laborers of the Kshatriya caste.

The untouchables and coolies are poor and impuissant laborers who have unjustly been repressed and victimized by those in society who have the power to control and dominate them. As colonial subjects, Bakha and Gangu are doubly colonized, “slaves of slaves.” Bakha’s situation in Untouchable is much more complex than that of Munoo, because as an untouchable he is permanently denigrated to servitude and placed at the lowest possible rung of society by a tradition against which he cannot rebel.

Although a Hindu, he has been placed outside the Hindu caste system. Like all untouchables, he is destined to clean human excrement and sweep dirt and litter from the homes of upper-caste Hindus and public places. Because of his occupation, he must not touch upper-caste Hindus for fear of defiling them. Indeed, no salvation exists for Bakha.

That he would remain imprisoned because of a cruel tradition is at the heart of the tragedy. Untouchable, compact in structure and inspired by James Joyce ‘s experiment in Ulysses (1922), as Naik and Marlene Fisher have noted, is a tragedy in the classic sense, with the exception that Bakha neither rebels nor resorts to incendiary action against social injustice and religious bigotry as classical tragic heroes do.

C. J. George has noted in Mulk Raj Anand: His Art and Concerns that Bakha’s story is based on Anand’s childhood friend, a sweeper boy of the same name, a point also supported by Anand’s own essay “The Story of My Experiment with a White Lie.” Lakha’s three children–Bakha, Sohini, and Rakha–carry on the ancestral profession of cleaning up dung, but Rakha virtually lives in dung.

The Brahmin priest’s alleged attempt to make advances to Sohini, Bakha’s visit to the temple and the alleged pollution of the temple, and the episode of “pollution by touch” all reveal the social and moral injustices of society. Bakha must announce “Posh, posh, sweeper is coming” whenever he is on the move.

When Bakha is slapped on the face and his jalebis are thrown out, his realization is painfully authentic: “Untouchable! I am an untouchable.” A young Brahmin priest accuses Bakha of polluting him but does not hesitate to touch Sohini. Bakha’s self-reflective mood helps him to trace the sociohistoric origin of his ancestry to the peasant stock who because of the “serfdom of thousands of years” had changed their occupation.

Bakha calmly reflects on the three possible alternatives offered for the eradication of servitude: the Gandhian path of wisdom, sympathy, forgiveness, and pacifism; the teachings of Christianity as interpreted by Colonel Hutchinson of the Salvation Army; and the boon of modern scientific and technological progress. Anand clearly sees the futility of all three positions.

The message of Christ, for example, got intermingled with colonialism and imperialism. The assumption that the flush system will eradicate the evil of untouchability is as fanciful and misleading as the Gandhian discipline of self-abnegation and self-sacrifice.

Whereas Bakha is an innocent victim of the old Indian tradition of casteism, the fate of Munoo lies in the hands of the modernist forces–British colonial rule, the capitalistic attitudes of rich mill owners, and the snobbery of the Anglo-Indian community. The Coolie deals with the life of an orphan boy from a village in the Kangra Valley.

The young boy runs away from abuse and poverty. (The story of the tragic loss of young Munoo’s innocence to the world of experience is a common theme in Anand’s works.) Leaving his ancestral village, Munoo comes to Sham Nagar and becomes a domestic servant in the house of Babu Nathu Ram.

Munoo is beaten, abused, and humiliated. One night he escapes to Daulatpur to work in Seth Prabha Dyal’s pickle factory. With the collapse of the bankrupt Seth, Munoo is able to make his way to Bombay, where he joins the inhabitants of urban slums.

Two important events that change the course of Munoo’s life in Bombay are the labor strike in Sir George Cotton Mills and the outbreak of Hindu-Muslim disturbances. Munoo gets hurt in an automobile accident. An Anglo-Indian lady, Mrs. Mainwaring, brings him to Simla, where he works as a rickshaw puller.

Jack Lindsay has maintained that the last chapter, in which Munoo ends up in Simla, is not an integral part of the total structure of the book. While disagreeing with their criticisms about the last chapter of the book, Saros Cowasjee maintains that “it was right of Anand to retrieve his hero from the horrors of Bombay and to help him to regain his identity.

” Also, bringing Munoo to Simla is consistent with the total design of the book, for it allows Anand to complete his portrait of British India by focusing on the colonial center of power.

The portrait of Mr. England is as significant as the portrayal of colonized and dehumanized Indians such as Babu Nathu Ram and the emaciated subaltern, Mrs. Mainwaring. Munoo ends his life, however, not in Simla, the summer capital of the government of India, but in the natural setting of the hills. The village of his birth, Sham Nagar; Daulatpur; Bombay; and Simla are stages in Munoo’s journey through the hell of someone who cannot fight the power structures of society.

The beautiful Simla Hills remind Munoo of his childhood home in the Kangra Valley, but nature, like society, is of little or no help other than facilitating the final release from life.

In Two Leaves and a Bud , Gangu, a peasant from the Punjab, migrates with his family to Assam to work as an indentured laborer on the Macpherson Tea Estate. The novel focuses on the treatment of plantation workers by their colonial masters, the owners of tea gardens.

The plantation coolies lead a life of degrading poverty, wretchedness, misery, and despair. Their inhuman working conditions are morally debilitating; the plantation workers are not only poorly paid but also often abused, beaten, and forced to work unusually long hours. Each worker has been promised a piece of land for cultivation, but the plantation owner Reggie Hunt’s lust for women must be satisfied to obtain this favor.

John de la Havre, the medical officer, and Barbara, colonial official Croft-Cooke’s daughter, are the only two humane voices that lament the merciless exploitation of Indian coolies by their compatriots.

The three volumes of the Lalu trilogy portray the life of Lal Singh, the youngest of Nihal Singh’s six children. Nandpur, where The Village is set, reflects once again Anand’s fascination with rural settings. The simplicity, naturalness, vividness, and authenticity of his portrayal of the village; the untainted realism and the long descriptive passages of the novel; and the simple and casual details offered are characteristic of ballad and folklore.

“The Village, ” remarks Alastair Niven, “is perhaps the most rounded portrait of village and rural life that the Indian novel in English offers us.” Yet, Nandpur has its unsavory side and problems that are also typical of Indian village life.

By placing Nandpur in the historical context of British India, Anand shows that the structure of village life and economy was directly threatened by colonization and modernization. Nihal Singh’s poverty, like that of so many other farmers in Nandpur, allows moneylenders such as Chaman Lal to thrive in the village. The collusive role of Sardar Bahadur Harbans Singh is as repugnant as is that of villager Mahant Nandigar.

Lalu rebels against religious customs and blind tradition, and the reader knows through Lalu Mahant’s hypocrisy and lechery, Sardar’s cruel and authoritarian ways, and the moneylender’s rapaciousness and cunning. The peasants’ lack of awareness of the self-constricting and cruel tradition that has impeded social progress is also revealing. Finally, Lalu’s affection for Maya forces the landlord to file a false charge of theft against him and forces him to escape by joining the army.

In the British Indian Army, Lalu gets the affections of Kirpu, Dhanoo, and Lachman Singh–all surrogate father figures. He receives the news of his own father’s death on the eve of the Ferozepur Brigade’s departure for the war in Europe.

In 1939 Anand married Kathleen Van Gelder, an actress. The following year Across the Black Waters was published. It does not have a conventional plot, but the narrative is carefully organized around a series of movements that takes place in France during World War I.

In his review of the novel, Dobree observed that Anand’s book was the only war book showing “Indian troops in France” but that it was not as “a description of war” that the book achieved its interest, “but as a revelation of what the average Sepoy felt and thought during that strange adventure.”

The book is not really about World War I but is an account of the feelings and perceptions of the war theater and of Europe by Lalu and other Indian soldiers. Dorothy Figuiera in an essay for The Indian Imagination notes Anand’s strategy of reversal; instead of a European experiencing the exoticism of the colonial “Other,” the Asian subject experiences the exoticism of the European Other.

Anand’s remarkable strategy of placing Indian soldiers, the simple unsophisticated peasants from the Punjab, in their colonial masters’ homeland enables them to see the drama of violent savagery and the meaning and purpose of war, death, and destruction. The Indian soldiers are greatly impressed by the manners and the ideas of the French people. These mercenary Indian soldiers–ill trained, ill equipped, and ill paid, especially when compared to their British counterparts–serve for the most part as cannon fodder.

Anand, as Figuiera observes, indicts “the British High Command’s incompetence and questions the morality of Indian troops to fight a British war.” Anand’s main point is that India’s right to participate in a global war should be decided not by the colonial regime but by Indians.

Lalu is wounded and taken prisoner by the Germans. He then returns to India to become a revolutionary in The Sword and the Sickle. Lalu’s hope of being rewarded by the British government for his service in the war is dashed. He finds that his mother is dead and that the family house has been auctioned. Professor Verma recruits him to work as an organizer of peasants.

Thus, Lalu and his beloved Maya leave Punjab for Rajgarh, the new locale of the novel. The Sword and the Sickle is a sociopolitical novel and combines two major concerns: the social problem of the eviction of peasants by landlords and the political problem of national freedom. Anand’s interest in Indian peasantry owes much to Leo Tolstoy , Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru.

The novel received laudatory reviews in England from such critics as Orwell. By presenting through Lalu’s experience some of the major political ideologies of revolution and social reconstruction–communism, socialism, and Gandhian thought–Anand depicted the various options of bringing about change. With his expanded consciousness, Lalu understands “the need to curb malice, the need for men to stand together as brothers.”

The Big Heart shows Anand’s effort to portray the conflict between tradition and modernity, and the laborer and the machine. His greatest triumph in the novel is the creation of the tragic figure of Ananta, a coppersmith who is accidentally killed by Ralia, another coppersmith, who, because he is unemployed, is wrecking the machines.

The conflict between the two groups of the coppersmith community in Amritsar, the ironmongers who represent the machine and the voice of modernity, and the thathiars, the workers who represent tradition, is at the center of the plot. At another level, one finds out that wealth divides the thathiar community of the same Kshatriya caste into adversarial classes.

Thus, in the class war the socioeconomic category of class gets interchanged with the socioreligious category of caste. Anand’s main point in the novel is that in the worker-owner relationship, industrialization without humanistic values represents profitability, greed, and exploitation. One can blame the machine or Ralia for Ananta’s death, but Anand the novelist philosophizes about Ananta’s death.

The philosopher-poet Puran Singh explains to Janki on the eve of Ananta’s death the nature of change and social progress: the old order must die in order to make room for the new. (The figure of the poet is a recurring figure in Anand’s novels, starting with Untouchable and continuing to The Big Heart.)

The poet’s discourse on death, change, and progress is intended to provide some solace to Janki; but in a larger sense Ananta and the poet are two convergent voices of Anand himself. While the poet emphasizes the need for love, compassion, and bhakti as a basis for ideal brotherhood, Ananta stands not only for the machine and progress but also for the “big heart.”

The critical debate about Anand’s achievement as a novelist in the postindependence period is focused on the assumption that independent India would have offered Anand the opportunity to develop new aspirations for his vision and art. Anand returned from England as a well-established writer, but the dissolution of the colonial fantasy did not in any way impede his progress as a novelist.

With the dissolution of the British Empire, Anand did not suddenly become bereft of subject matter for his novels. After India’s independence from colonial subjugation, Anand seized the opportunity to reflect on the psychohistorical formation of himself in an attempt to achieve self-consciousness.

The mature Anand was a philosopher and historian of culture, but he did not compromise with institutions of social injustice, oppression, and subjugation. He continued his search for a just humanistic order. Anand’s “self-search” led to the exploration of the historical and psychological processes that went into the making of himself as a man and as a novelist.

Anand’s novel Private Life of an Indian Prince (1953) is a dramatic departure from the subject of untouchables, coolies, and peasants, and yet the theme is similar, for Maharaja Ashok Kumar is also a victim. Cowasjee maintains that this novel is Anand’s “most impressive work.” It has some similarities with Manohar Malgonkar’s The Princes (1963).

In 1948 Anand and Kathleen divorced. In 1949 he married Shirin Vajifdar, a classical dancer. A few years later, he began a projected seven-novel series.

The novels of the Seven Ages of Man series have shown distinct and enduring vitality. Of the projected seven novels, Anand completed four: Seven Summers (1951), Morning Face (1968), Confession of a Lover (1976), and The Bubble (1984). He also wrote Little Plays of Mahatma Gandhi (1991), the first part of the seven-part volume And So He Plays His Part.

The remaining two novels were to be “The World Too Large, a World Too Wide” and “Last Scene.” In the autobiographical novels of The Seven Ages series, Anand has used memory as a powerful tool for re-creating pictures and images of his own life.

The Seven Ages series is particularly memorable for Anand’s creation of Krishan Chander. The treatment of his hero’s childhood combines the romantic notion of innocence and experience. The TLS reviewer of Seven Summers describes Krishan Chander “as a Freudian baby [that] was never born in English fiction of the twenties and thirties.”

This Freudian characterization of Krishan Chander is more fully developed in Morning Face , a work in which Anand, influenced by Samuel Butler and George Bernard Shaw , explores fictively the relationship between his father and his family.

A proper grasp of Krishan Chander’s relationship with his family, especially his father, calls for a grasp of history, psychobiography, and psychoanalysis. Anand has subverted the Krishna myth in the novel, since Krishan Chander is not the Krishna of Hindu mythology but a human Krishna, a hero/antihero. However, his affinity with the mythical Krishna gives Krishan Chander a playfulness, vigor, and freedom not enjoyed by a Butlerian or a Joycean figure.

The young Krishan’s unreserved involvement with women and his growth as a radical nationalist are further developed in Confession of a Lover. During his four years of study at Khalsa College, Amritsar, the young Krishan Chander develops a strong interest in Gandhian ideas, nationalist politics, and poetry.

Two notable influences on Krishan are poet Allama Iqbal, who inspires him to write poetry, and Professor Henry, who introduces him to Indian metaphysics. The most painful and probably the most tragic part of the narrative is Krishan’s love for Yasmin, who becomes pregnant with his child but dies.

Although the novel Morning Face won Anand the prestigious Sahitya Akademy Award, The Bubble, the last volume that Anand completed in the proposed series, has been regarded as a greater work. D. Riemenschneider, for example, maintains that The Bubble “is perhaps the most ambitious book Anand has written so far because it tells us so much about the author himself.” The Bubble deals with Krishan Chander’s stay in England, his pursuit of a Ph.D. in philosophy, his love affairs, his quest for identity, and his search for the meaning of life.

He confronts his own past, examines the sources of his emotional and ideological transformation, assesses the basis of his political thought, seeks validity for his philosophy of humanism, and attempts to redefine his philosophy of art in the larger context of the East-West synthesis. As a young artist in the making, he comes in contact with the important writers of the 1930s. Thus, Conversations in Bloomsbury is partly an expanded version of some of the ideas underlying the narrative of The Bubble.

The two works together show Anand’s great disillusionment with those English intellectuals who no doubt championed the cause of liberty but did not support the struggle for Indian freedom. Anand’s essay Apology for Heroism directly deals with his search for truth and the formation of his intellectual thinking.

Works of Mulk Raj Anand

Novels

-

- Untouchable (1935,London: Wishart)

-

- Coolie (1936, London: Lawrence & Wishart)

-

- Two Leaves and a Bud (1937, London: Lawrence & Wishart)

-

- The Village (1939, London: Jonathan Cape)

-

- Lament on the Death of a Master of Arts (1939, Lucknow: Naya Sansar)

-

- Across the Black Waters (1939, London: Jonathan Cape)

-

- The Sword and the Sickle (1942, London: Jonathan Cape)

-

- The Big Heart (1945, London: Hutchinson)

-

- Seven Summers: the Story of an Indian Childhood (1951, London: Hutchinson)

-

- The Private Life of an Indian Prince (1953, London: Hutchinson)

-

- The Old Woman and the Cow (1960, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- The Road (1961, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- Death of a Hero: Epitaph for Maqbool Sherwani (1964, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- Morning Face (1968, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- Confession of a Lover (1976, New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann)

-

- Gauri (1976, New Delhi: Orient Paperbacks)

-

- The Bubble (1984, New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann)

-

- Nine Moods of Bharata: Novel of a Pilgrimage (1998, New Delhi: Arnold Associates)

-

- Reflections on a White Elephant (2002, New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications)

Short story collections

-

- The Lost Child and Other Stories (1934, London: J. A. Allen)

-

- The Barber’s Trade Union and Other Stories (1944, London: Jonathan Cape)

-

- The Tractor and the Corn Goddess and Other Stories (1947, Bombay: Thacker)

-

- Reflections on the Golden Bed and Other Stories (1953, Bombay: Current Book House)

-

- The Power of Darkness and Other Stories (1959, Bombay: Jaico)

-

- Lajwanti and Other Stories (1966, Bombay: Jaico)

-

- Between Tears and Laughter (1973, New Delhi: Sterling)

-

- Selected Stories of Mulk Raj Anand (1977, New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann, ed. M. K. Naik)

-

- Things Have a Way of Working Out and Other Stories (1998, New Delhi: Orient)

-

- The Gold Watch

-

- Duty

Children’s literature

-

- Indian Fairy Tales (1946, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- The Story of India (1948, Bombay: Kutub)

-

- The Story of Man (1952, New Delhi: Sikh Publishing House)

-

- More Indian Fairy Tales (1961, Bombay: Kutub)[25]

-

- The Story of Chacha Nehru (1965, New Delhi: Rajpal & Sons)

-

- Mora (1972, New Delhi: National Book Trust)

-

- Folk Tales of Punjab (1974, New Delhi: Sterling)

-

- A Day in the Life of Maya of Mohenjo-daro (1978, New Delhi: Children Book Trust)

-

- The King Emperor’s English or the Role of the English Language in the Free India (1948, Bombay: Hind Kitabs)

-

- Some Street Games of India (1983, New Delhi: National Book Trust)

-

- Chitralakshana: Story of Indian Paintings (1989, New Delhi: National Book Trust)

Books on Arts

-

- Persian Painting (1930, London: Faber & Faber)

-

- The Hindu View of Art (1933, Bombay: Asia Publishing House, London: Allen & Unwin)

-

- How to Test a Picture: Lectures on Seeing Versus Looking (1935)

-

- Introduction to Indian Art (1956, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, author: Ananda Coomaraswamy) (editor)

-

- The Dancing Foot (1957, New Delhi: Publications Division)

-

- Kama Kala: Some Notes on the Philosophical Basis of Hindu Erotic Sculpture (1958, London: Skilton)

-

- India in Colour (1959, Bombay: Taraporewala)

-

- Homage to Khajuraaho (1960, Bombay: Marg Publications) (co-authored with Stella Kramrisch)

-

- The Third Eye: A Lecture on the Appreciation of Art (1963, Chandigarh: University of Punjab)

-

- The Volcano: Some Comments on the Development of Rabindranath Tagore’s Aesthetic Theories (1968, Baroda: Maharaja Sayajirao University)

-

- Indian Paintings (1973, National Book Trust)

-

- Seven Little Known Birds of the Inner Eye (1978, Vermont: Wittles)

-

- Poet-Painter: Paintings by Rabindranath Tagore (1985, New Delhi: Abhinav Publications)

-

- Splendours of Himachal Heritage (editor, 1997, New Delhi: Abhinav Publications)

Letters

-

- Letters on India (1942, London: Routledge)

-

- Author to Critic: The Letters of Mulk Raj Anand (1973, Calcutta: Writers Workshop, ed. Saros Cowasjee)

-

- The Letters of Mulk Raj Anand (1974, Calcutta: Writers Workshop, ed. Saros Cowasjee)

-

- Caliban and Gandhi: Letters to “Bapu” from Bombay (1991, New Delhi: Arnold Publishers)

-

- Old Myth and New Myth: Letters from Mulk Raj Anand to K. V. S. Murti (1991, Calcutta: Writers Workshop)

-

- Anand to Alma: Letters of Mulk Raj Anand (1994, Calcutta: Writers Workshop, ed. Atma Ram)

Other works

-

- Curries and Other Indian Dishes (1932, London: Desmond Harmsworth)

-

- The Golden Breath: Studies in five poets of the new India (1933, London: Murray)

-

- Marx and Engels on India (1937, Allahabad: Socialist Book Club) (editor)

-

- Apology for Heroism: An Essay in Search of Faith (1946, London: Lindsay Drummond)

-

- Homage to Tagore (1946, Lahore: Sangam)

-

- On Education (1947, Bombay: Hind Kitabs)

-

- Lines Written to an Indian Air: Essays (1949, Bombay: Nalanda Publications)

-

- The Indian Theatre (1950, London: Dobson)

-

- The Humanism of M. K. Gandhi: Three Lectures (1967, Chandigarh: University of Punjab)

-

- Critical Essays on Indian Writing in English (1972, Bombay: Macmillan)

-

- Roots and Flowers: Two Lectures on the Metamorphosis of Technique and Content in the Indian English Novel (1972, Dharwad: Karnatak University)

-

- The Humanism of Jawaharlal Nehru (1978, Calcutta: Visva-Bharati)

-

- The Humanism of Rabindranath Tagore: Three Lectures (1978, Aurangabad: Marathwada University)

-

- Is There a Contemporary Indian Civilisation? (1963, Bombay: Asia Publishing House)

-

- Conversations in Bloomsbury (1981, London: Wildwood House & New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann)

-

- Pilpali Sahab: Story of a Childhood under the Raj (1985, New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann); Pilpali Sahab: The Story of a Big Ego in a Small Boy (1990, London: Aspect)

-

- Voices of the Crossing – The impact of Britain on writers from Asia, the Caribbean and Africa. Ferdinand Dennis, Naseem Khan (eds), London: Serpent’s Tail, 1998. Mulk Raj Anand: p. 77 “A Writer in Exile.”

Notable awards

-

- International Peace Prize – 1953

-

- Padma Bhushan – 1967

-

- Sahitya Akademi Award – 1971 (for Morning Face)

AWARDS

In 1952, hand was awarded the Internatioilal Peace Prize of the World Peace Council for promoting peace among the nations through his literary works. In 1967, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan by the President of India for disticguished service to art and literature.

In 1978, he Non the E.M. Forster award of Rs.3000 for his novel Confession ofa Lover which was adjusted the best book of creative literature in the English Language.’

This was the first annual award instituted by MIS Arnold Heinemann. 2.5 THE THIRTIES MOVEMENT “Among the Indo-English novelists,” observes hniah Gowda, “Mulk Raj Anand is the most conspicuously committed writer.. . Perhaps the best word for it is the plainest: it is propaganda writing.

“‘ The Propaganda novel in the true sense is one so dominated by its author’s ulterior purpose that the propaganda cannbt be ignored, and normally one who dislikes that line of propaganda would find the book unreadable. Such a novel, Gowda opines, cannot rank among the great works of literature. In a similar vein, Chetan Kamani complains of the extra-literary intentions of the novelist:

“The trouble with Anand is that he is not able to hide his proletarian sympathies “2 These ‘determined’ detractors of Anand, and some others, charge him of having used the artistic medium of the novel for pure propaganda.

Indoctrination, they hold, does not go with the creative process and aesthetic experience. Anand is not deterred by such-criticism:

“I do not in the least mind criticism, even Life and Work of Mulk Raj Anand Untouchable already been rewarded by the fact that they have gone into so many languages of the world in spite of their truffilness and exposure of many shams, hypocrisies and orthodoxies of 1ndia. “3 This is true, for in his fiction Anand was heeding his artistic conscience than following any pre-conceived formula.

And that accounts for the abiding appeal of his novels. Untouchable, as also some other early writings of Anand, cannot be fully appreciated unless studied in relation to the movement of the nineteen-thirties in Western Europe. For, as a writer he was shaped in the Thirties when several problems bogged the intellectuals.

The problem that Anand “tried to face as a writer was not strictly a private, but a private-public problem.”4 As it was, he found it impossible to maintain aloofness from politics in the post-World War Europe.

Anand stayed in London for over two decades, from 1924 to 1945; he was therefore deeply influenced by the Progressive Movement in literature that flourished in the Thirties. In London, Anand came under numerous literary, political and social influences and it is in them that the sources of his synthesis of Marxist and humanist thought can be seen.

“You will find that amorphous as my books are,” writes Anand, “I did stick to the novel form, more or less, as an imaginative interpretation of Indian life rather than use it as a vehicle to sermonize.

And the posing of the problems of human beings in the 30s by people like Malraux, Celine and Hemingway gave the necessary sense of discrimination to my own treatment of the predicament of our people as against the European view.”5 He was an overt nationalist and championed the socialist cause in his fiction in common with many European and American writers of the day.

The peculiar conditons during the early decades of the century in Europe and elsewhere put a great pressure on the writers to sympathize with the social cause. The complacency following the First World War, based on the erroneous belief that ‘ the League of Nations was going to preserve peace and security, was suddenly exploded, leaving a feeling of loss and disenchantment. There was complete erosion of human values.

Another event that had a profound influence on writers like hand was the General strike of 1926 in the Great Britain. It made people conscious of the class war between haves and ha-re-nots in modem civilization. On his amval in England, Anand had admired Britain for her achievements in science and technology. Living through the strike, this illusion of his was shattered with a bang.

He increasingly came to realize that the scientific and technological discoveries if controlled bq a select band of people need not result in social benefits. “And it was no use speculating on the beneficence of science,” avers hand, “if its discoveries were to be manipulated to their own advantage by a small group of individuals who controlled the key industries and had an absolute say in matters of domestic and foreign policy.” The object of the General Strike was to attain specific rights for the mine workers, in a way it was a proletarian challenge to the government and its capitalist bias.

Anand and a group of his colleagues sided with the workers; they felt dismayed at the fallure of the strike. The strike had revealed the reactionary character of the English State “that it could put back human progress for a thousand years.”

7 Anand felt convinced “that the people of Britain, no less than the people of India, had yet to win thelr liberty.” After the destruction wrought by the First World War, European society had plunged anew into the shadows of economic depression and cynical mood. The econon~ic depression caused disastrous effects; it gave rise to unemployment that brought in its fold unending distress and appalling misery.

The rise of Fascism in Italy under Mussolini and the Nazi power in Germany in 1933 Life and Work of under Hitler reflected the paralysis of the Western democracies.

The Japanese Mulk Raj Anand aggression on Manchuria in 193 1, the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in 1935, the extinction of Spanish Republic at the hands of Germany and Italy in 1936-37, all in succession tolled the death knell of the league of Nations. Such a distintegrating world disillusioned the intellectual of the day; he strove for a commitment that would restore order and save his world from the existing chaos.

The writer was not only absorbing the atmospehre as a participant but also seemed readily inclined to reflect it in his writing.

Alarmed at the situation the intellectuals of the West prominently led by Maxim Gorky of Russia, Romain Rolland of France, Thomas Mann of Germany, and E.M. Forster of England assembled in Paris in 1935. They raised the voice of liberty as Shelley and Dickens had done in their own times.

“I want greater freedom for writers,” declared Forster, “both as creators and critics for the . . maintenance of ~ulture.”~ He appealed to the writers to be courageous and sensitive to fulfil their public calling; he urged them to come forward and arouse the people to act and struggle for creating a just and humane society.

Tl~e conference was dominated by the writers with a soc~alist background, or having some affiliation with communism They posed a premonition of a threatening situation, caused by the aggressive imperialism of the day.

The psychology working in the background was the moving force that impelled the writers to use their talents against fascism and write for the working classes. Inspired by these ideas some Indian students studying in England assembled in London a kw months after the Paris Conference and formed the Progressive Writers Association.

Their meetings were attended and occasionally addressed by Ralph Fox, Karnford and Caudwell. They fiamed a mamfesto of the Association, which was finalized, amongst others by Mulk Raj Anand and Sajjad Zaheer. Sajjad Zaheer who played a prominent role in the organization vividly recalls his association with Anand:

“I have had the good fortune of having known Mulk.. .since 1930, when we were both young and in our twenties and were students in England. In 1935, Anand and I, together with a few other young Indians founded the Indian Progressive Writers Movement, spreading to almost all the great languages of India, blessed and supported by such eminent figures as Tagore and Premchand.

” The progressive writers believed that the principal function of literature was to reflect and express the aspirations and fundamental problems of the toiling masses and ultimately help in the formation of a socialist society. Even those who were not Marxists adhered to the idea of a basic social transformation and political independence.

A new content is discerned in literature, which not only bears out a radically revolutionary character but also a basically new rationale for such a change. “That truth alone should matter to a writer,” says Anand in his essay “Why I Write?,” “that this truth should become imaginative truth without losing sincerity. The novel should interpret the truth of life, from felt experience, and not from book^.”‘^

The Progressive Movement then has a reaction against the esoteric and ~nwardlooking art of the nineteen-twenties. In England, it began with the publication of Michael Robert’s anthologies, New Signarures and New Country which grouped Auden, Spender, Day Lewis, Isherwood and Edward Upward together for the first time. These writers were responsible for making social realism and tendentious literature of revolt fashionable in both Europe and America. It was during the same time that Anand was working on his novel Coolie.

He essentially shared the political and s~ial philosophy of the left wing intellectuals: “there was ample ~~nfirmation ln the thinking hd ofthe younger writers life Aragon, Malraw Auden, Spender, Day Lewis and *at the~uestions they were asking themselves were more or less Uniouchable similar to ours in India, and, irrespective of race and colour, we shared similar concepts and aspired towards hndred objects.”

” Lefr Review, an important organ of the new writers, carried extracts from the then unpublished Coolie. The particular conditions of the Thirties account for many close resemblances between Anand, Mahatma Gandhi and George Orwell; both had much m common. esp. a passionate sense of social justice, “a recognition, more than a recognition.

indeed knowledge–of the innumerable frustrations and suppressions. Both men hated the social prejudices that helped to maintain the oppressive status quo; the class system in England, the caste system in 1ndia.”I2 Moreover, both the writers shared a profound dislike of colonialism. In tone and temper, Orwell’s Road to Wlgan Pier carried the same burden as Anand’s Coolie.

One of the notable consequences of this movement was a growing rejection of the aestheitc theory of “art for art’s sake.” Anand has felt, from the very initial stages of his awareness of the human predicament, that the writer cannot shut himself in an ivory tower; he cannot stand on a high perch, but has to go into the raging storm itself, to be with the people to ally himself with their many sorrows and little joys.

The purpose of the novel, according to Anand, is to change mankind, and through mankind society. He is vehmently opposed to the formalists or aesthetes who hold that art, though influenced by life, is essentially governed by its inner logic and not by outside forces. Nor has he any sympathy with the writers who are self-centred subjectivists indulging merely in petty variations of Proustian aestheticism The Thirties movement defined in specific terms the position of the artists and the functions of his art.

In Apology for Heroism, Anand places the writer on a very high pedestal, glorifying him as “precisely the man who can encompass the whole of life.”I3 He is superior to the moralist, the scientist and the politician, each of whom takes a limited view of man, whle the writer “is uniquely fitted to aspire to be a whole man to attain, as far as possible, a more balanced perspective of life.”

l4 A novelist like any other artist is concerned chiefly with the truth. And he reveals it not like the philosopher who does it in a cold statement of dogma but only in terms of life, rendered through the devices of dramatization.

Anand, like Lawrence, Gorky, and Eric Gill, believes that the work of a genuine creative writer is inspired by a mission. He seems to be in full agreement with Arnold’s dictum that literature at bottom is the criticism of like. He is strongly committed to his creed, and in his opinion “any miter who said that he was not interested in a condition humane was either posing or yielding to a fanatical love of isolationism–a perverse and clever defense of the adolescent desire to be different.

“I5 The Thirties movement proved to be a watershed in the literary sensibility in Europe. It shook the writers from age-old slumber and awakened them to the realization of new possibilities, whlch had so far eluded them.

The early fiction of Anand was truly representative of the movement. His fictional world depicted not the feudal splendors and mysticism of traditional Indian literature, but the hard and suffering lives of the millions of his countrymen. Anand thus ushered in the realistic fiction.

In the choice of themes, therefore, Anand is unquestionably an innovator. He is the first novelist writing in English to choose as his raw material the lower-class life of the Indian masses. In Untouchable and Coolie, he almost dreads the flight of imagination, feels shy of soaring high and keeps close to the ground with a vengeance. He does not hesitate to turn the floodlight on the darkest spots in Indian.

My Other Biography

Casinuucasino, nice! Found some of my favorite games here. The signup process was easy, and I’ve had a smooth overall experience. Might stick around for a while. Worth checking out casinuucasino if you are a regular casino player.