Table of Contents

-

- Introduction

-

- Early Life or Oscar Wills Wilde

-

- University Education of Oscar Wills Wilde

-

- Apprenticeship of an aesthete

-

- Prose Writing: 1886-1891

-

- Theatrical Career : 1892-1895

-

- Trials

-

- Imprisonment

-

- Biographies of Oscar Wills Wilde

-

- Selected works

Introduction

Oscar Fingal O’Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and his criminal conviction for gross indecency for homosexual acts.

Oscar Wilde’s parents were Anglo-Irish intellectuals in Dublin. In his youth Wilde learned to speak fluent French and German. At university, he read Greats; he demonstrated himself to be an exceptional classicist, first at Trinity College Dublin, then at Magdalen College, Oxford. He became associated with the emerging philosophy of aestheticism, led by two of his tutors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin. After university, Wilde moved to London into fashionable cultural and social circles.

He tried his hand at various literary activities: he wrote a play, published a book of poems, lectured in the United States and Canada on the new “English Renaissance in Art” and interior decoration, and then returned to London where he lectured on his American travels and wrote reviews for various periodicals. Known for his biting wit, flamboyant dress and glittering conversational skill, Oscar Wilde became one of the best-known personalities of his day. At the turn of the 1890s he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays, and incorporated themes of decadence, duplicity, and beauty into what would be his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Oscar Wilde returned to the drama, writing Salome (1891) in French while in Paris, but it was refused a licence for England due to an absolute prohibition on the portrayal of Biblical subjects on the English stage. Undiscouraged, Oscar Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late-Victorian London.

At the height of his fame and success, while An Ideal Husband (1895) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) were still being performed in London, Oscar Wills Wilde issued a civil writ against John Sholto Douglas, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry for criminal libel. The Marquess was the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. The libel hearings unearthed evidence that caused Oscar Wilde to drop his charges and led to his own arrest and criminal prosecution for gross indecency with men. The jury was unable to reach a verdict and so a retrial was ordered. In the second trial Oscar Wilde was convicted and sentenced to two years’ hard labour, the maximum penalty, and was jailed from 1895 to 1897. During his last year in prison he wrote De Profundis (published posthumously in abridged form in 1905), a long letter that discusses his spiritual journey through his trials and is a dark counterpoint to his earlier philosophy of pleasure. On the day of his release he caught the overnight steamer to France, never to return to Britain or Ireland. In France and Italy he wrote his last work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), a long poem commemorating the harsh rhythms of prison life.

Early life of Oscar Wills Wilde

The Oscar Wilde family home on Merrion Square

Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin (now home of the Oscar Wilde Centre, Trinity College), the second of three children born to an Anglo-Irish couple: Jane, née Elgee, and Sir William Wilde. Oscar was two years younger than his brother, William (Willie) Wilde.

Jane Wilde was a niece (by marriage) of the novelist, playwright and clergyman Charles Maturin, who may have influenced her own literary career. She believed, mistakenly, that she was of Italian ancestry, and under the pseudonym “Speranza” (the Italian word for ‘hope’), she wrote poetry for the revolutionary Young Irelanders in 1848; she was a lifelong Irish nationalist. Jane Wilde read the Young Irelanders’ poetry to Oscar and Willie, inculcating a love of these poets in her sons.Her interest in the neo-classical revival showed in the paintings and busts of ancient Greece and Rome in her home.

Sir William Wilde was Ireland’s leading oto–ophthalmologic (ear and eye) surgeon and was knighted in 1864 for his services as medical adviser and assistant commissioner to the censuses of Ireland. He also wrote books about Irish archaeology and peasant folklore. A renowned philanthropist, his dispensary for the care of the city’s poor at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin (TCD), was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road. On his father’s side Oscar Wilde was descended from a Dutch soldier, Colonel de Wilde, who came to Ireland with King William of Orange‘s invading army in 1690, and numerous Anglo-Irish ancestors. On his mother’s side, Wilde’s ancestors included a bricklayer from County Durham, who emigrated to Ireland sometime in the 1770s.

Oscar Wills Wilde was baptised as an infant in St. Mark’s Church, Dublin, the local Church of Ireland (Anglican) church. When the church was closed, the records were moved to the nearby St. Ann’s Church, Dawson Street. A Catholic priest in Glencree, County Wicklow, also claimed to have baptised Wilde and his brother Willie.

In addition to his two full siblings, Wilde had three half-siblings, who were born out of wedlock before the marriage of his father: Henry Wilson, born in 1838 to one woman, and Emily and Mary Wilde, born in 1847 and 1849, respectively, to a second woman. Sir William acknowledged paternity of his children and provided for their education, arranging for them to be reared by his relatives.

The family moved to No 1 Merrion Square in 1855. With both Sir William and Lady Wilde’s success and delight in social life, the home soon became the site of a “unique medical and cultural milieu”. Guests at their salon included Sheridan Le Fanu, Charles Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt, William Rowan Hamilton and Samuel Ferguson.

Oscar Wills Wilde’s sister, Isola Francesca Emily Wilde, was born on 2 April 1857. She was named in tribute to Iseult of Ireland, wife of Mark of Cornwall and lover of the Cornish knight, Sir Tristan. She shared the name Francesca with her mother, while Emily was the name of her maternal aunt. Oscar would later describe how his sister was like “a golden ray of sunshine dancing about our home”and he was grief stricken when she died at the age of nine of a febrile illness. His poem “Requiescat” was written in her memory; the first stanza reads:

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

Until Oscar Wills Wilde was nine Wilde was educated at home, where a French nursemaid and a German governess taught him their languages. He joined his brother Willie at Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, which he attended from 1864 to 1871. At Portora, although he was not as popular as his older brother, Wilde impressed his peers with the humorous and inventive school stories he told. Later in life he claimed that his fellow students had regarded him as a prodigy for his ability to speed read, claiming that he could read two facing pages simultaneously and consume a three-volume book in half an hour, retaining enough information to give a basic account of the plot. He excelled academically, particularly in the subject of classics, in which he ranked fourth in the school in 1869. His aptitude for giving oral translations of Greek and Latin texts won him multiple prizes, including the Carpenter Prize for Greek Testament. He was one of only three students at Portora to win a Royal School scholarship to Trinity in 1871.

In 1871, when Oscar Wills Wilde was seventeen, his elder half-sisters Mary and Emily died aged 22 and 24, fatally burned at a dance in their home at Drumacon, Co Cavan. One of the sisters had brushed against the flames of a fire or a candelabra and her dress caught fire; in various versions the man she was dancing with carried her and her sister down to douse the flames in the snow, or her sister ran her down the stairs and rolled her in the snow, causing her own muslin dress to catch fire too.

Until his early twenties, Wilde summered at Moytura House, a villa his father had built in Cong, County Mayo. There the young Wilde and his brother Willie played with George Moore.

University education of Oscar Wills Wilde: 1870s

Trinity College, Dublin

Oscar Wills Wilde left Portora with a royal scholarship to read classics at Trinity College, Dublin (TCD), from 1871 to 1874, sharing rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde. Trinity, one of the leading classical schools, placed him with scholars such as R. Y. Tyrell, Arthur Palmer, Edward Dowden and his tutor, Professor J. P. Mahaffy, who inspired his interest in Greek literature. As a student Wilde worked with Mahaffy on the latter’s book Social Life in Greece. Wilde, despite later reservations, called Mahaffy “my first and best teacher” and “the scholar who showed me how to love Greek things”. For his part, Mahaffy boasted of having created Wilde; later, he said Wilde was “the only blot on my tutorship”.

The University Philosophical Society also provided an education, as members discussed intellectual and artistic subjects such as the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne weekly. Wilde quickly became an established member – the members’ suggestion book for 1874 contains two pages of banter sportingly mocking Wilde’s emergent aestheticism. He presented a paper titled Aesthetic Morality.

At Trinity,Oscar Wills Wilde established himself as an outstanding student: he came first in his class in his first year, won a scholarship by competitive examination in his second and, in his finals, won the Berkeley Gold Medal in Greek, the university’s highest academic award. He was encouraged to compete for a demyship (a half-scholarship worth £95 (£9,400 today) per year) to Magdalen College, Oxford – which he won easily.

Magdalen College, Oxford

At Magdalen, he read Greats from 1874 to 1878, and from there he applied to join the Oxford Union, but failed to be elected.

Attracted by its dress, secrecy and ritual, Wilde petitioned the Apollo Masonic Lodge at Oxford, and was soon raised to the Sublime Degree of Master Mason. During a resurgent interest in Freemasonry in his third year, he commented he “would be awfully sorry to give it up if I secede from the Protestant Heresy”.Oscar Wills Wilde’s active involvement in Freemasonry lasted only for the time he spent at Oxford; he allowed his membership of the Apollo University Lodge to lapse after failing to pay subscriptions.

Catholicism deeply appealed to him, especially its rich liturgy, and he discussed converting to it with clergy several times. In 1877, Oscar Wills Wilde was left speechless after an audience with Pope Pius IX in Rome. He eagerly read the books of Cardinal Newman, a noted Anglican priest who had converted to Catholicism and risen in the church hierarchy. He became more serious in 1878, when he met the Reverend Sebastian Bowden, a priest in the Brompton Oratory who had received some high-profile converts. Neither Mahaffy nor his father, who threatened to cut off his funds, thought much of the plan; but Wilde, the supreme individualist, balked at the last minute from pledging himself to any formal creed, and on the appointed day of his baptism into Catholicism, sent Father Bowden a bunch of altar lilies instead. Wilde did retain a lifelong interest in Catholic theology and liturgy.

While at Magdalen College, Wilde became well known for his role in the aesthetic and decadent movements. He wore his hair long, openly scorned “manly” sports, though he occasionally boxed, and decorated his rooms with peacock feathers, lilies, sunflowers, blue china and other objets d’art. He once remarked to friends, whom he entertained lavishly, “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china.” The line quickly became famous, accepted as a slogan by aesthetes but used against them by critics who sensed in it a terrible vacuousness. Some elements disdained the aesthetes, but their languishing attitudes and showy costumes became a recognised pose. Wilde was once physically attacked by a group of four fellow students, and dealt with them single-handedly, surprising critics. By his third year Wilde had truly begun to develop himself and his myth, and considered his learning to be more expansive than what was within the prescribed texts. He was rusticated for one term, after he had returned late to a college term from a trip to Greece with Mahaffy.

Wilde did not meet Walter Pater until his third year, but had been enthralled by his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, published during Wilde’s final year in Trinity. Pater argued that man’s sensibility to beauty should be refined above all else, and that each moment should be felt to its fullest extent. Years later, in De Profundis, Wilde described Pater’s Studies… as “that book that has had such a strange influence over my life”. He learned tracts of the book by heart, and carried it with him on travels in later years. Pater gave Wilde his sense of almost flippant devotion to art, though he gained a purpose for it through the lectures and writings of critic John Ruskin. Ruskin despaired at the self-validating aestheticism of Pater, arguing that the importance of art lies in its potential for the betterment of society. Ruskin admired beauty, but believed it must be allied with, and applied to, moral good. When Wilde eagerly attended Ruskin’s lecture series The Aesthetic and Mathematic Schools of Art in Florence, he learned about aesthetics as the non-mathematical elements of painting. Despite being given to neither early rising nor manual labour, Wilde volunteered for Ruskin’s project to convert a swampy country lane into a smart road neatly edged with flowers.

Wilde won the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem “Ravenna“, which reflected on his visit there in the previous year, and he duly read it at Encaenia. In November 1878, he graduated with a double first in his B.A. of Classical Moderations and Literae Humaniores (Greats). Wilde wrote to a friend, “The dons are ‘astonied‘ beyond words – the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!”

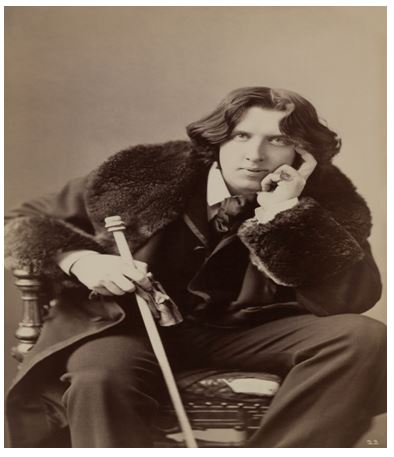

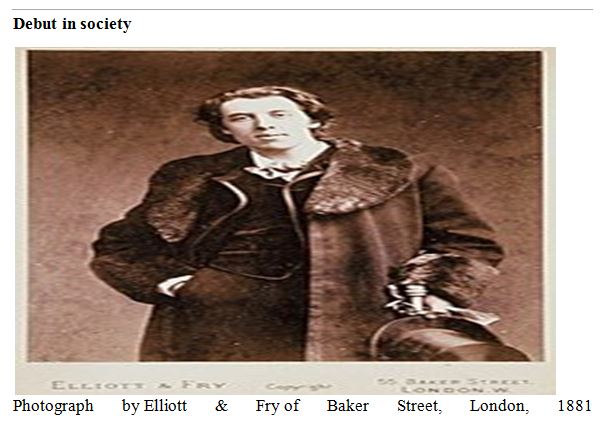

Apprenticeship of an aesthete: 1880s

1881 caricature in Punch, the caption reads: “O.W.”, “Oh, I eel just as happy as a bright sunflower, Lays of Christy Minstrelsy, “Æsthete of Æsthetes!/What’s in a name!/The Poet is Wilde/But his poetry’s tame.”

After graduation from Oxford, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met again Florence Balcombe, a childhood sweetheart. She became engaged to Bram Stoker and they married in 1878. Wilde was disappointed but stoic. He wrote to Balcombe remembering; “the two sweet years – the sweetest years of all my youth” during which they had been close. He also stated his intention to “return to England, probably for good”. This he did in 1878, only briefly visiting Ireland twice after that.

Unsure of his next step, Wilde wrote to various acquaintances inquiring about Classics positions at Oxford or Cambridge. The Rise of Historical Criticism was his submission for the Chancellor’s Essay prize of 1879, which, though no longer a student, he was still eligible to enter. Its subject, “Historical Criticism among the Ancients” seemed ready-made for Wilde – with both his skill in composition and ancient learning – but he struggled to find his voice in the long, flat, scholarly style. Unusually, no prize was awarded that year.

With the last of his inheritance from the sale of his father’s houses, he set himself up as a bachelor in London. The 1881 British Census listed Wilde as a boarder at 1 (now 44) Tite Street, Chelsea, where Frank Miles, a society painter, was the head of the household. Lillie Langtry was introduced to Wilde at Frank Miles’ studio in 1877. The most glamorous woman in England, Langtry assumed great importance to Wilde during his early years in London, and they remained close friends for many years; he tutored her in Latin and later encouraged her to pursue acting.[59] She wrote in her autobiography that he “possessed a remarkably fascinating and compelling personality”, and “the cleverness of his remarks received added value from his manner of delivering them.”

Wilde regularly attended the theatre and was especially taken with star actresses such as Ellen Terry and Sarah Bernhardt. In 1880 he completed his first play, Vera; or, The Nihilists, a tragic melodrama about Russian nihilism, and distributed privately printed copies to various actresses whom he hoped to interest in its sole female role. A one-off performance in London was advertised in November 1881 with Mrs. Bernard Beere as Vera, but withdrawn by Wilde for what was claimed to be consideration for political feeling in England.

He had been publishing lyrics and poems in magazines since entering Trinity College, especially in Kottabos and the Dublin University Magazine. In mid-1881, at 27 years old, he published Poems, which collected, revised and expanded his poems.

Though the book sold out its first print run of 750 copies, it was not generally well received by the critics: Punch, for example, said that “The poet is Wilde, but his poetry’s tame” By a tight vote, the Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism. The librarian, who had requested the book for the library, returned the presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology. Biographer Richard Ellmann argues that Wilde’s poem “Hélas!” was a sincere, though flamboyant, attempt to explain the dichotomies the poet saw in himself; one line reads: “To drift with every passion till my soul / Is a stringed lute on which all winds can play”.

The book had further printings in 1882. It was bound in a rich, enamel parchment cover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on hand-made Dutch paper; over the next few years, Wilde presented many copies to the dignitaries and writers who received him during his lecture tours.

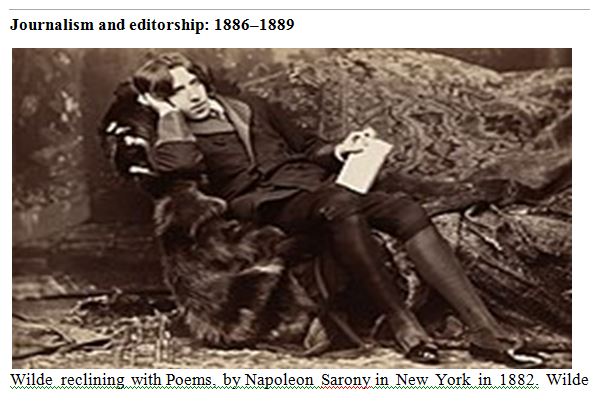

Prose writing: 1886–1891

Journalism and editorship: 1886–1889

Criticism over artistic matters in The Pall Mall Gazette provoked a letter in self-defence, and soon Wilde was a contributor to that and other journals during 1885–87. Although Richard Ellmann has claimed that Wilde enjoyed reviewing, Wilde’s wife would tell friends that “Mr Wilde hates journalism”. Like his parents before him, Wilde supported Ireland’s cause, and when Charles Stewart Parnell was falsely accused of inciting murder, he wrote a series of astute columns defending the politician in the Daily Chronicle.

His flair, having previously been put mainly into socialising, suited journalism and rapidly attracted notice. With his youth nearly over and a family to support, in mid-1887 Wilde became the editor of The Lady’s World magazine, his name prominent on the cover. He promptly renamed it as The Woman’s World and raised its tone, adding serious articles on parenting, culture, and politics, while keeping discussions of fashion and arts. Two pieces of fiction were usually included, one to be read to children, the other for the adult readers. Wilde worked hard to solicit good contributions from his wide artistic acquaintance, including those of Lady Wilde and his wife, Constance, while his own “Literary and Other Notes” were themselves popular and amusing.

The initial vigour and excitement which he brought to the job began to fade as administration, commuting and office life became tedious. At the same time as Wilde’s interest flagged, the publishers became concerned about circulation: sales, at the relatively high price of one shilling, remained low. Increasingly sending instructions to the magazine by letter, Wilde began a new period of creative work and his own column appeared less regularly. In October 1889, Oscar Wills Wilde had finally found his voice in prose and, at the end of the second volume, Wilde left The Woman’s World. The magazine outlasted him by only a year. Wilde’s period at the helm of the magazine played a pivotal role in his development as a writer and facilitated his ascent to fame. Whilst Wilde the journalist supplied articles under the guidance of his editors, Wilde the editor was forced to learn to manipulate the literary marketplace on his own terms.

During the 1880s, Oscar Wills Wilde was a close friend of the artist James McNeill Whistler and they dined together on many occasions. At one of these dinners, Whistler produced a bon mot that Wilde found particularly witty, Wilde exclaimed that he wished that he had said it. Whistler retorted “You will, Oscar, you will.” Herbert Vivian—a mutual friend of Wilde and Whistler—attended the dinner and recorded it in his article The Reminiscences of a Short Life, which appeared in The Sun in 1889. The article alleged that Wilde had a habit of passing off other people’s witticisms as his own—especially Whistler’s. Wilde considered Vivian’s article to be a scurrilous betrayal, and it directly caused the broken friendship between Wilde and Whistler. The Reminiscences also caused great acrimony between Wilde and Vivian, Wilde accusing Vivian of “the inaccuracy of an eavesdropper with the method of a blackmailer”and banishing Vivian from his circle. Vivian’s allegations did not diminish Wilde’s reputation as an epigrammatic. London theater director Luther Monday recounted some of Wilde’s typical quips: he said of Whistler that “he had no enemies but was intensely disliked by his friends”, of Hall Caine that “he wrote at the top of his voice”, of Rudyard Kipling that “he revealed life by splendid flashes of vulgarity”, of Henry James that “he wrote fiction as if it were a painful duty”, and of Marion Crawford that “he immolated himself on the altar of local colour”.

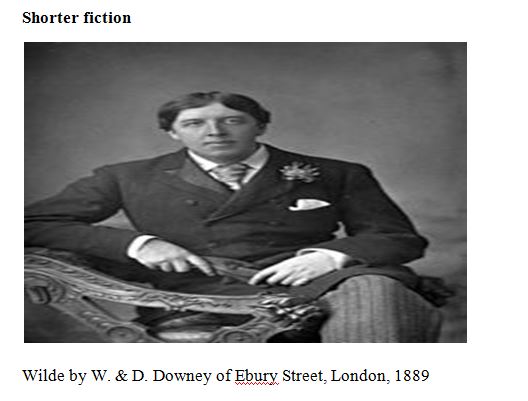

Wilde by W. & D. Downey of Ebury Street, London, 1889

Oscar Wills Wilde had been regularly writing fairy stories for magazines. He published The Happy Prince and Other Tales in 1888. In 1891 he published two more collections, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories, and in September A House of Pomegranates was dedicated “To Constance Mary Wilde”. “The Portrait of Mr. W. H.“, which Wilde had begun in 1887, was first published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in July 1889. It is a short story which reports a conversation in which the theory that Shakespeare’s sonnets were written out of the poet’s love of the boy actor “Willie Hughes“, is advanced, retracted, and then propounded again. The only evidence for this is two supposed puns within the sonnets themselves.

The anonymous narrator is at first sceptical, then believing, finally flirtatious with the reader: he concludes that “there is really a great deal to be said of the Willie Hughes theory of Shakespeare’s sonnets.” By the end fact and fiction have melded together. Arthur Ransome wrote that Wilde “read something of himself into Shakespeare’s sonnets” and became fascinated with the “Willie Hughes theory” despite the lack of biographical evidence for the historical William Hughes’ existence. Instead of writing a short but serious essay on the question, Wilde tossed the theory to the three characters of the story, allowing it to unfold as background to the plot — an early masterpiece of Wilde’s combining many elements that interested him: conversation, literature and the idea that to shed oneself of an idea one must first convince another of its truth. Ransome concludes that Oscar Wills Wilde succeeds precisely because the literary criticism is unveiled with such a deft touch.

Though containing nothing but “special pleading” – it would not, he says “be possible to build an airier castle in Spain than this of the imaginary William Hughes” – we continue listening nonetheless to be charmed by the telling. “You must believe in Willie Hughes,” Wilde told an acquaintance, “I almost do, myself.”

Imprisonment

When first I was put into prison some people advised me to try and forget who I was. It was ruinous advice. It is only by realising what I am that I have found comfort of any kind. Now I am advised by others to try on my release to forget that I have ever been in a prison at all. I know that would be equally fatal. It would mean that I would always be haunted by an intolerable sense of disgrace, and that those things that are meant for me as much as for anybody else – the beauty of the sun and moon, the pageant of the seasons, the music of daybreak and the silence of great nights, the rain falling through the leaves, or the dew creeping over the grass and making it silver – would all be tainted for me, and lose their healing power, and their power of communicating joy. To regret one’s own experiences is to arrest one’s own development. To deny one’s own experiences is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life. It is no less than a denial of the soul.

De Profundis

Further information: De Profundis (letter)

Having been convicted in “one of the first celebrity trials”, Wilde was incarcerated from 25 May 1895 to 18 May 1897.

He first entered Newgate Prison in London for processing, then was moved to Pentonville Prison, where the “hard labour” to which he had been sentenced consisted of many hours of walking a treadmill and picking oakum (separating the fibres in scraps of old navy ropes), and where prisoners were allowed to read only the Bible and The Pilgrim’s Progress.

A few months later Oscar Wills Wilde was moved to Wandsworth Prison in London. Inmates there also followed the regimen of “hard labour, hard fare and a hard bed”, which wore harshly on Wilde’s delicate health. In November he collapsed during chapel from illness and hunger. Oscar Wills Wilde right ear drum was ruptured in the fall, an injury that later contributed to his death. He spent two months in the infirmary.

Richard B. Haldane, the Liberal MP and reformer, visited Wilde and had him transferred in November to Reading Gaol, 30 miles (48 km) west of London on 23 November 1895. The transfer itself was the lowest point of his incarceration, as a crowd jeered and spat at him on the platform at Clapham Junction railway station (in 2019 a rainbow plaque was unveiled at the station recalling this event). He spent the remainder of his sentence at Reading, addressed and identified only as “C.3.3” – the occupant of the third cell on the third floor of C ward.